Space

A legacy left by a dead rover

Published

12 months agoon

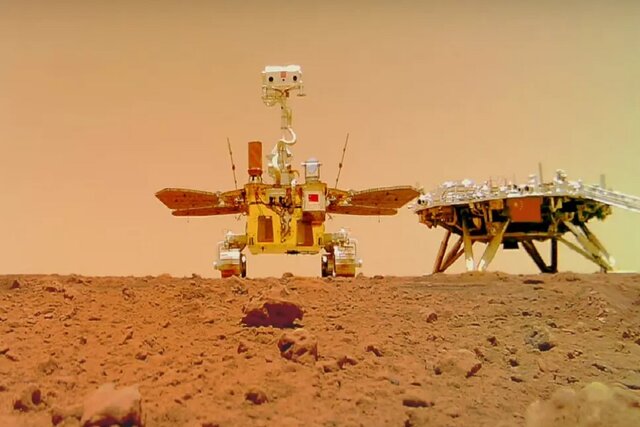

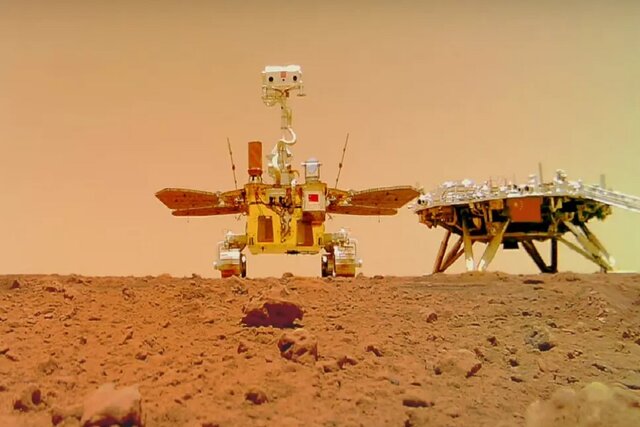

A legacy left by a dead rover. China’s Zhurang rover may be dead, but its legacy lives on.

A legacy left by a dead rover

China has just confirmed that the country’s first Mars rover may have been permanently disabled due to the accumulation of Martian dust on its surfaces.

This Chinese rover has been hibernating since May last year.

This month, however, Chinese officials broke their silence on the Jurong mission, announcing that the rover would not be able to emerge from its planned hibernation.

The accumulation of Martian dust on the solar panels has caused Jurong to shut down, and this rover cannot receive energy from the relatively mild sun that reaches the Red Planet.

Although China has not confirmed the end of Jurong’s mission, there is a possibility that the country’s rover will not be able to wake up again. However, Jurong has collected a lot of data that allows scientists to gain important information about Mars.

Read More: Two stars that will become black holes in 18 billion years!

New findings change our understanding of Mars’ recent past

For example, a new study suggests that salty water may have existed in the warmer, low-lying regions of Mars once closer to now.

The new study, published in the journal Science Advances, came from an analysis of Martian sand dunes collected by the Jurong rover.

Using data from the rover’s imaging camera as well as its chemical measuring instrument, the scientists in this new paper analyzed cracks and other surface features of the Martian dunes.

A press release indicates that they found that the hills were probably formed by the melting of frozen waters 400,000 years ago.

The findings show that Mars had a wetter climate in the modern era than previously thought. They could also provide data for future missions to the Red Planet looking for signs of ancient microbial life.

Analysis of fissures in Martian dunes

Scientists generally agree that Mars probably had large bodies of water billions of years ago, such as the ancient lake at Jezero Crater, where NASA’s Endurance rover is currently searching for signs of life.

However, less is known about Martian surface water in recent millennia. Some indirect geological evidence suggests that water processes still occur on the planet’s surface, but more research is needed.

In this context, the new research team collected Jurang data to better understand modern hydroclimatic conditions on Mars.

Specifically, they analyzed the rover’s data on the salt-rich dunes of the Utopia Planitia region in the northern hemisphere of Mars where Jurong landed in May 2021, looking for signs of ancient microbes that could have adapted to high salinity.

Jurong rover missions may or may not have ended. Either way, its scientific legacy will live on for years to come.

You may like

-

Artificial intelligence could explain why we haven’t seen extraterrestrials yet

-

Can humans endure the psychological torment of living on Mars?

-

Black holes may be the source of mysterious dark energy

-

Scientists’ understanding of dark energy may be completely wrong

-

Why the James Webb telescope does not observe the beginning of the universe?

-

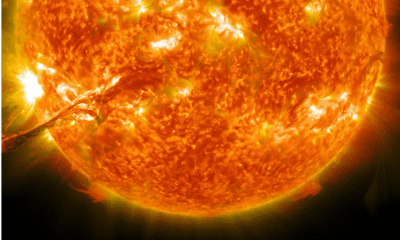

How can solar storms destroy satellites so easily?

Space

Artificial intelligence could explain why we haven’t seen extraterrestrials yet

Published

7 hours agoon

26/04/2024

Artificial intelligence could explain why we haven’t seen extraterrestrials yet

Artificial intelligence shows us its presence in thousands of different ways. This technology has capabilities such as accessing huge data sources, detecting financial frauds, driving cars and even suggesting music. On the other hand, artificial intelligence chatbots have amazing performance; But all this is just the beginning.

Can we figure out how fast artificial intelligence is developing? If the answer is no, does it include the notion of a large filter? Fermi’s paradox refers to the difference between the high probability of the existence of advanced civilizations and the absence of evidence of their presence. Many solutions have been proposed as to why this discrepancy exists. One of these hypotheses is the “big filter”.

The Great Filter is a hypothetical event or situation that prevented intelligent life from becoming an interplanetary or interstellar entity and could even lead to its destruction. Such events can include climate change, nuclear war, asteroid collisions, supernova explosions, plague, or even other catastrophic events; But what about the rapid growth of artificial intelligence?

A new study in the journal Acta Astronautica shows that artificial intelligence is becoming artificial superintelligence (ASI), which could be one of the great filters. The title of this article is as follows: “Is artificial intelligence a great filter that makes advanced civilizations rare in the world?” The author of this article is Michael Garrett from the Faculty of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Manchester.

Artificial intelligence as a big filter can prevent biological species from accessing interplanetary and interstellar spaces.

Artificial intelligence as a big filter can prevent biological species from accessing interplanetary and interstellar spaces.

Some people believe that the Great Filter will prevent a technological species like us from becoming a multi-planetary species. This is bad news because species with only one home are at risk of extinction or stagnation. According to Garrett, species without a backup planet are in a race against time. he writes:

Such a filter appears before civilizations reach multiplanetary stability and presence, suggesting that the typical lifespan of an advanced civilization is less than 200 years.

If the above hypothesis is true, it can be proved why we have not found any traces of technology or other evidence of extraterrestrial intelligence; But what does this hypothesis say about the path of human technology? If we face a limit of 200 years and this limit is due to ASI, what will be our fate?

Garrett also emphasizes the need to create legal frameworks for the development of artificial intelligence on Earth and the development of a multi-planetary society to deal with existing threats.

Artificial superintelligence (ASI) can completely replace the human race

Many scientists and thinkers say that we are on the threshold of a huge transformation. Artificial intelligence is revolutionizing how things are done; Much of this transformation takes place behind the scenes. AI looks set to eliminate millions of jobs, and when combined with robotics, there are no boundaries. Certainly, these developments will be an obvious concern.

However, there are more systemic and deeper concerns. Who writes the algorithms? Will artificial intelligence be able to recognize to some extent? It can be said with almost certainty that this will be possible. Do competitive algorithms destroy strong democratic societies? Will open communities continue to stagnate? Will ASI decide for us and if so who will be held accountable?

The above questions are increasing without any clear end. Stephen Hawking always warned that if artificial intelligence evolves independently, it can destroy the human race. In 2017, he said in a conversation with Wired magazine:

I am afraid that artificial intelligence will completely replace humans. If people can design computer viruses now, perhaps in the future someone will be able to design an artificial intelligence that improves and reproduces itself. This type of intelligence will be a new form of life that can surpass humans.

The combination of artificial intelligence and robotics can become a threat to humans.

The combination of artificial intelligence and robotics can become a threat to humans.

Hawking may be considered one of the most significant figures of warning about artificial intelligence, But he is not alone. The media is full of discussions and warnings as well as articles about the capabilities of artificial intelligence. The most important caveat is that ASI can become rogue. Some people consider this hypothesis to be science fiction, but Garrett doesn’t think so. According to his writing:

Concerns about artificial super-intelligence (ASI) and its going rogue in the future are a major issue. Combating this possibility will become a growing field of research for AI leaders in the coming years.

If AI had no advantage, the problem would be simpler; But the technology offers a variety of benefits, from improved medical imaging and diagnostics to safer transportation systems. The trick for governments is to allow benefits to grow while controlling harm. According to Garrett, this issue is especially important in the fields of defense and national security, where moral development and responsibility are important.

The problem is that we and our governments are not sufficiently prepared. There has never been such a thing as artificial intelligence, and no matter how hard we try to conceptualize and understand its path, we will not reach the expected result. Therefore, if we are in such a situation, probably other biological organisms in other parts of the world have the same conditions. The emergence of artificial intelligence and artificial superintelligence could be a cosmic issue, making it a good candidate for the big filter. The danger that ASI can pose is that it may one day no longer need the biological life that created it.

According to Garrett’s explanation, ASI systems, by reaching the technological singularity, can overtake biological intelligence and evolve at a rate that even outpaces their own monitoring mechanisms and ultimately lead to unexpected and unintended consequences that are unlikely to be compatible with biological ethics and interests. to be

Life on multiple planets could diminish the threat of artificial intelligence.

Life on multiple planets could diminish the threat of artificial intelligence.

How can ASI free itself from the pesky biological life that has captured it? may engineer a deadly virus; or prevent the production and distribution of agricultural products or even lead to the collapse of the nuclear power plant and start a war.

It is not yet possible to speak definitively about the possibilities, as the realm of artificial intelligence is uncertain. Hundreds of years ago, cartographers were drawing monsters in unexplored regions of the world, and now that’s what we’re doing. Garrett’s analysis is based on the assumption that ASI and humans occupy the same space; But if we can reach a multiplanetary state, this scenario will change. Garrett writes:

For example, multiplanetary biological species can draw on the independent experiences of different planets and avoid the single-point failure imposed by a single-planetary civilization by increasing the diversity of survival strategies.

If we can spread the risk over multiple planets around multiple stars, we can protect ourselves from the worst possible consequences of ASI. This distributed model increases the resilience of biological civilizations against artificial intelligence disasters by creating redundancy. If one of the planets or bases occupied by future humans fails to survive the ASI technological singularity, the others may survive and learn from the failure.

A multi-planetary situation could also be beyond the ASI’s rescue. Based on Garrett’s hypothetical scenarios, we can try more experiences with AI while keeping it limited. Consider an AI on an isolated asteroid or dwarf planet that doesn’t have access to the resources it needs to escape and can thus be limited. By Garrett:

This scenario applies to isolated environments where the effects of advanced artificial intelligence can be explored without the immediate risk of global annihilation.

However, a complex issue arises here. Artificial intelligence is advancing at an ever-increasing rate, while human efforts to become a multi-planetary species are at a slow pace. According to Garrett, the incompatibility between the rapid development of artificial intelligence and the slow development of space technology is very clear.

The speed of artificial intelligence is much faster than space travel

The difference here is that artificial intelligence is computational and informational, but space travel faces many physical obstacles that we still don’t know how to overcome. Human biological nature is an obstacle to space travel, but none of these obstacles limit artificial intelligence.

While artificial intelligence could theoretically improve its capabilities even without physical limitations, space travel faces limitations in energy, materials science, and the harsh realities of the space environment, Garrett writes.

Currently, artificial intelligence operates under the limitations set by humans; But this may not always be the case. We still don’t know when AI might turn into ASI, But we cannot ignore this possibility. This issue can lead to two intertwined conclusions.

If Garrett is right, humans should try harder for space travel. It may seem far-fetched, but knowledgeable people know that Earth will not be habitable forever. If man does not expand his civilization into space, he may be destroyed by his own hand or by the hand of nature. However, reaching the moon and Mars can promise future steps.

The second conclusion is related to the legalization and supervision of artificial intelligence; A difficult task in a world where mental illness can take control of entire nations and lead to an increase in wars. Although industry stakeholders, policymakers, independent experts, and their governments are warning about the need for legislation, creating a universally accepted legal framework is difficult, writes Garrett.

In fact, humanity’s perpetual disparity makes the goal of controlling artificial intelligence uncontrollable. Regardless of how fast we develop strategies, AI can grow even faster. In fact, without applicable law, there is a reason to believe that artificial intelligence is not only a threat to future civilization but a threat to the entire advanced civilizations.

The continuation of intelligent and conscious life in the world may depend on the effective and timely implementation of legal regulations and technological efforts.

Space

Can humans endure the psychological torment of living on Mars?

Published

2 days agoon

24/04/2024

Can humans endure the psychological torment of living on Mars?

Alyssa Shannon is a registered nurse at UC Davis Medical Center. One day, on his way to the university hospital, NASA called him and told him that he had been selected for a mission to Mars. That same morning, Nathan Jones, an emergency room physician in Springfield, received a similar call. He immediately thought of his family and told himself that if you accept this opportunity, you will have to let them go. However, he couldn’t turn down NASA’s opportunity and convinced himself that Mars was his destiny.

The Mars Crew Health and Performance Probe Analogue Mission, or CHAPEA for short, will not actually send selected individuals to Mars, but rather will accurately simulate the first human journey to Mars and pave the way for sending the first humans to Mars, possibly by 2040.

According to NASA, humans will one day travel to Mars. In 2018, NASA estimated that the first humans would land on Mars “by the late 2020s at the latest.” The date for the first human mission has changed slightly, but despite the technical hurdles, it will definitely happen one day. Rachel McCulley, until recently the deputy director of NASA’s Mars campaign, has compiled a list of 800 problems that must be solved before the first human mission can be launched.

Many of the items on the list deal with the mechanical problems of transporting people to a planet that never gets closer than 54.6 million kilometers to Earth. Keeping people alive in toxic soil and unbreathable air, bombarded by solar radiation and galactic cosmic rays, without access to immediate and safe communications to bring them back to Earth more than a year and a half later, are some of the challenges of a trip to Mars.

Other problems involve technical details too obscure for McCulley to explain. But he has no doubts that NASA will overcome these challenges. Of course, what NASA and no one else knows yet is whether humanity will be able to overcome the psychological torment of living on Mars.

CHAPEA’s mission addresses human rather than technical questions. For 378 days, four ordinary volunteers will experience the conditions of human life on Mars as much as possible. They received instructions, feedback, and full supervision from Mission Control. These people eat astronaut food, perform basic experiments, perform maintenance tasks, answer endless surveys, and enjoy organized downtime. This level of extreme realism is necessary to ensure that the experiment correctly determines whether humans can live millions of kilometers away from their acquaintances.

The experimenters wanted to know if the crew could eat astronaut food for hundreds of days without losing their appetite, weight or positive attitude. Can they live in a confined space with strangers? Can they maintain a cohesive professional environment without contact with the ground? Such questions are of the utmost importance because no mission to Mars can succeed if Martians cannot maintain their health, happiness, and, most importantly, their sanity.

If Martians cannot maintain their mental health, no Mars mission will be successful

NASA’s goal of the simulated mission was to see if subjects could thrive in an environment designed to closely resemble Mars. NASA launched the program in August 2021 with a “Mars Calls” announcement on its website. Participation in CHAPEA, unlike most NASA missions, was open to the general public, or at least to a broad segment of the public: citizens or permanent residents between the ages of 30 and 55 with a master’s degree or higher in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Applicants were told that the experience was “mentally difficult”.

NASA offered four golden tickets to travel to a simulated settlement called Dune Alpha; The 158 square meter building was built inside a large warehouse at the Johnson Space Center in Houston. This settlement was built using 3D printing technology and instead of ink, Martian regolith was used. NASA did not have sufficient amounts of Martian regolith, so a special orange material called lavacrete was used, which was removed layer by layer from a 3D printer.

The residence has four identical cells that serve as bedrooms, a lounge, a television, and four chairs. There are also several desks with computer monitors, a medical station, and an agricultural garden in the settlement. Garden plants considered for mental health: Growing plants may have “psychological benefits for astronauts living in an isolated environment far from Earth,” says one researcher. The rooms have different heights to avoid the monotony of the space. The yard is shaped like a box filled with red sand and has two treadmills for the crew to practice “space walking”. The walls of the courtyard are covered with murals of Martian rocks and there are no windows.

The duration of the trial is the most obvious violation of the truth. Orbital geometry dictates that the shortest round-trip mission to Mars would take about 570 days, and this scenario might occur once every 15 years. A typical trip to Mars would take at least 800 days.

NASA has declined to disclose details of the 378-day confinement, which ends on July 6, 2024, to preserve the integrity of the experiment. NASA only emphasized that participants would experience “resource limitations, equipment failures, communication delays, and other environmental stressors.” For example, the crew on the Mars mission must form lasting emotional bonds with strangers and rely on each other for comfort. The crew must respond to any emergency situation on their own without any intervention or guidance. They must cope with not being able to care for a sick child, a grieving spouse, or a dying parent.

Future travelers to Mars must not only endure all these conditions alone but also pursue this opportunity with a determined and honest purpose in order to earn the privilege of long-duration space travel. They must accept that for at least 570 days, they will be the most isolated humans in the history of the world.

How does isolation affect performance?

Alyssa Shannon had dreamed of Mars since she was a child and knew she could endure the hardships and long periods of isolation. Nathan Jones also felt that this mission was designed for him. But professional observers of America’s space programs, a group of NASA historians, ethicists, and advisers who spend much of their careers studying the future of space exploration, have raised the question: What does NASA want to learn from the CHAPEA mission that it doesn’t already know?

The psychological damage of social distancing is well understood. Everyone knows what isolation does to a person. Johnson Schwartz, a philosophy professor who studies the ethics of space exploration, says: “What ambiguity is left when you lock people in a room for a year? “Just because the room is painted to look like Mars doesn’t mean the results will change.”

Monotony prevents people from performing the most basic tasks

The sources of Johnson Schwartz’s talk are 80 years of study in the field of isolation. The study of isolation began in World War II. At the time, the British Royal Air Force was concerned about the performance of pilots during solo flights. The officers noticed that the longer the pilot stayed in the air, the fewer submarines he detected. Psychologist Norman McWorth also recognized that the monotony of the mission is to blame for this. The monotony of the mission made the pilots unable to perform even the most basic tasks.

The results of Mackworth’s study inspired a series of studies by psychologist Donald O. Hebb from McGill University. Confirming McWorth’s findings, Hebb added new details. Monotony not only causes intellectual weakness but also leads to a “change in behavioral approach”. In Hebb’s experiment, his students slept and thought about their studies and personal problems. Then they would reminisce and recreate their movies or travels. Some also count to incredibly large numbers.

However all participants eventually lost the ability to focus. Several people also reported “blank periods” during which they thought about nothing. The next step was illusion. The hallucinations made people vulnerable, and long after the experiment was over, they believed the hallucinations were real.

Hebb’s findings inspired isolation studies. Individuals were confined in different locations and all results were consistent. In addition to attracting neuroscientists and psychologists, the experiments also attracted the attention and funding of the US intelligence community. The findings were included in “forced counter-espionage interrogations” or what is now called “brainwashing” or “psychological torture”.

Isolation studies were also closely monitored by the Air Force, which led the fledgling US space program before NASA was formed in 1958. Concerned that spaceflight might drive astronauts crazy, the Air Force conducted the first test similar to CHAPEA. The astronauts in this experiment were confined for a week in the cockpit of the spaceship, which was slightly larger than a coffin. The pilots were assigned a large number of technical tasks and were given large quantities of amphetamines.

The experiment followed a familiar pattern: initial high spirits gave way to a “gradual increase in irritability” and suddenly turned to “open hostility.” Many participants experienced hallucinations, with one pilot even abandoning the test after three hours and seeking psychiatric care.

In all isolation experiments, initial high spirits eventually gave way to irritability, violence, and hallucinations.

Several other similar studies were conducted before all research was stopped by the Mercury Space Program. Since the official start of the US space program in the early 1960s, astronauts have not suffered from any obvious psychological distress during successful solo missions, much to the relief of researchers. All long-duration space travel took place in Earth orbit, and crews were easily able to communicate with Earth. Government agencies continued to investigate the effects of isolation, but NASA did not.

NASA didn’t have a solution to the problem of isolation in space, and it didn’t need to, until half a century later when a new challenge arose: a human mission to a planet so far away that it would take at least 22 minutes for a cry for help to travel through the solar system. slow

The delay in communication worried CHAPEA crew members and families. All contact with the settlement is timed by the time it takes to send the information from Earth to Mars. Even exchanging short sentences like “How are you? “Good” also lasts at least 44 minutes.

But “44 minutes” is considered the best possible case, since every connection must flow through a connection point. Any information unit must wait in a digital queue, with priority given to the most urgent signals and smallest data packets. As a result, any normal human conversation with the earth is unthinkable. Also, there will be no contact during a three-week period in the middle of the experiment that marks the furthest distance between Earth and Mars.

The selected CHAPEA crew respected NASA’s decision on the mission, but if they wanted to better imagine the year ahead, they should study an earlier series of Mars simulations that shared some goals with the CHAPEA mission. For example, the HI-SEAS Analog Space Mission and Space Exploration Simulator in Hawaii simulated trips to the Moon and Mars missions between 2013 and 2017.

Civilians on the HI-SEAS mission were selected to live in a habitat in Hawaii for 12 months. The mission investigated and studied various nutritional and “psychosocial” benefits, as well as volunteers’ behavior and mental alertness and coping strategies developed to resist isolation.

Once Upon a Time I Lived on Mars is the memoir of Keith Green, one of the original HI-SEAS crew, and includes chapters entitled “On Boredom”, “In Isolation” and “Dreams of Mars, Dreams of Earth”. Green explains how the monotony changed his mission. “At that time mental fatigue had become my main state of mind,” he writes. The crew barely slept, were under constant surveillance, and scheduled leisure seemed a little forced.” The slightest provocation drove Greene mad, and he soon found himself missing out on everyday life on Earth.

The HI-SEAS mission followed the Mars 500 mission, the longest Mars simulation mission ever. Mars500, operated by the Russian Institute of Biomedical Problems, put a six-man crew together on a synthetic Mars for 520 days, between June 2010 and November 2011, in a synthetic spacecraft and a synthetic landing module.

Russian experimenters hypothesized that over time, astronauts would lose motivation, work less, and suffer from feelings of extreme isolation. After the experiment was over, the scientists announced that the hypotheses were “largely confirmed.” Crews lost confidence in their commanders and mission control, communication became poor, nutritional problems developed, and people became homesick and depressed. “It’s not easy to spend 520 days,” said Wang Yu , one of the participants who lost about 10 kilograms of weight and most of his hair. It is impossible to be happy all the time. “I am human, not a robot.”

Despite the previous results, the desire to simulate life on Mars still seems insatiable. CHAPEA is just one of dozens of NASA’s current analog experiments. One of Hera’s other missions is; A habitat that keeps four participants in isolation for 45 days. Since NASA ended participation in HI-SEAS, a variety of public and private organizations have continued the missions. The private association of the Mars Society has been operating several research bases in the Utah desert and the remote islands of northern Canada for years. Analogues of Mars have also been performed in Dome C of the Antarctic Plateau, the semi-arid region of northeastern Brazil, ice caves in Austria and Oman.

The effect of selected isolation is not the same as imposed isolation

The first travelers to Mars are likely to have the same psychological profile as Shannon, Jones, and two other participants: Ross Brockwell, a structural engineer and director of general operations, and Kelly Heston, a stem cell biologist. All four are NASA enthusiasts, in good physical health, and welcome long periods of isolation. These people themselves chose to spend a period of isolation and restriction.

Louise Hockley, an expert on social isolation, emphasizes that psychological responses are strongly influenced by whether isolation is chosen or imposed on individuals. A prisoner sentenced to life imprisonment usually suffers more than a monk who has taken a vow of silence. But Hockley points out that participants, no matter how well supported, are not autonomous. “Even if the crew is OK, what happens to the family that’s left behind?”

However, the designers of CHAPEA do not seem to have an understanding of the history of isolation and social isolation studies. In interviews, they also downplayed the findings of previous trials, including HI-SEAS. CHAPEA principal investigator Grace Douglas admitted she was “not entirely familiar” with the previous four-year trial, saying: “I don’t believe they met our performance criteria. “Our assessment is at a higher level of detail and will be more extensive.”

Rachel McCulley is NASA’s CHAPEA Funding Officer. When asked what he hopes to learn from the mission about human psychology, he said, “The big reason I funded the mission is that I want to know exactly how much food is needed for a Mars mission.”

But what about the psychological aspect of the mission? How do people cope with loneliness and monotony? McCauley is a solid fuel propulsion system engineer and his goal was to determine the spacecraft’s weight only. He could estimate the mass of everything, but he wanted to know how much food the four stressed astronauts would consume in 378 days and how much clothing they would need.

Investigating psychological issues is NASA’s second priority. Mathias, a historian of isolation, asks whether empirical logic can justify another study of isolation. In his opinion, these experiments are “a way to colonize Mars, or a form of wish-fulfillment, or, in other words, just a game of cosplay.” Analog experiments reflect utopian promises about a future for humans on Mars. A human mission to Mars is not the highest ambition in space programs, but a small step for mankind before a giant leap in the habitation of other planets.

The inhabitants of Mars will turn from humans into a modified species of “Martians”.

Five months before the CHAPEA call, Dennis Bushnell, a 60-year senior scientist at NASA’s Langley Research Center, published a paper on the future of space exploration, commercialization, and habitation. He says colonizing Mars has always been conceivable for colonizing humans. He notes that the prospect has gone from “very difficult” to “increasingly feasible” in recent years.

Bushnell predicts that Mars colonists will “become a modified species.” Travelers who colonize Mars will become Martians over time due to reduced exposure to heat and radiation. The ultimate promise of NASA’s Mars mission is a chance to start over, not exactly as humans, but as Martians. If we can settle on Mars and enjoy a carefree life with no regrets, it stands to reason that we should no longer be human, we should be Martians.

But Mathias likens the constant testing of Mars to a traumatic repetition. The compulsion to rebuild is an irrational and futile attempt to undo a deep injury. “The urge to try to recreate a perfect world is always repeating the same mistake we made here,” he says. “We are not looking for Mars, we are mourning for Earth.”

NASA released the official CHAPEA 1 crew portrait on June 25, 2023. From left to right: Anka Selario, Ross Brockwell, Kelly Heston, Nathan Jones.

NASA released the official CHAPEA 1 crew portrait on June 25, 2023. From left to right: Anka Selario, Ross Brockwell, Kelly Heston, Nathan Jones.

The four crew and two surrogates of the CHAPEA mission gathered together for a final month of training and evaluation a month before confinement to the settlement. Three weeks before arrival, NASA hosted a “Family Weekend” for the crew’s loved ones. Families visited the Johnson Space Center and interacted closely with the astronauts. The crew’s families agreed to share stress management techniques and pledged to keep in touch through a private Facebook page.

But Alyssa Shannon received a call five days before the mission began. He announced that NASA had removed him from the mission and had been replaced by U.S. Navy microbiologist Anka Selario. The reason for Alyssa’s removal was not released, but NASA investigators added that sometimes during final pre-mission tests, problems are found that are not “medically serious” but may pose a risk, such as an increased risk of kidney stones. Of course, this is just an example and the researchers refused to provide information.

On June 25, 2023, NASA’s YouTube channel broadcast footage of four CHAPEA 1 crew members standing on a platform in front of the settlement. Grace Douglas announced that the knowledge we gain here will help us send humans to Mars and return them home safely. Then, Douglas opened the simple white door of the settlement, the crew waved and entered. Douglas closed the door behind them. The happy voice of the crew could be heard from inside the settlement.

Black holes may be the source of mysterious dark energy

According to new research, supermassive black holes may carry the engines driving the universe’s expansion or mysterious dark energy. The existence of dark energy has been proven based on the observation of stars and galaxies, but so far no one has been able to find out its nature and source.

The familiar matter around us makes up only 5% of everything in the universe. The remaining 27% of the universe is made up of dark matter, which does not absorb or emit any light. On the other hand, a large part of the universe, or nearly 68% of it consists of dark energy.

According to new evidence, black holes may be the source of dark energy that is accelerating the expansion of the universe. This research is the result of the work of 17 astronomers in nine countries, which was conducted under the supervision of the University of Hawaii. British researchers from Raleigh Space, England’s Open University, and King’s College London collaborated in this research.

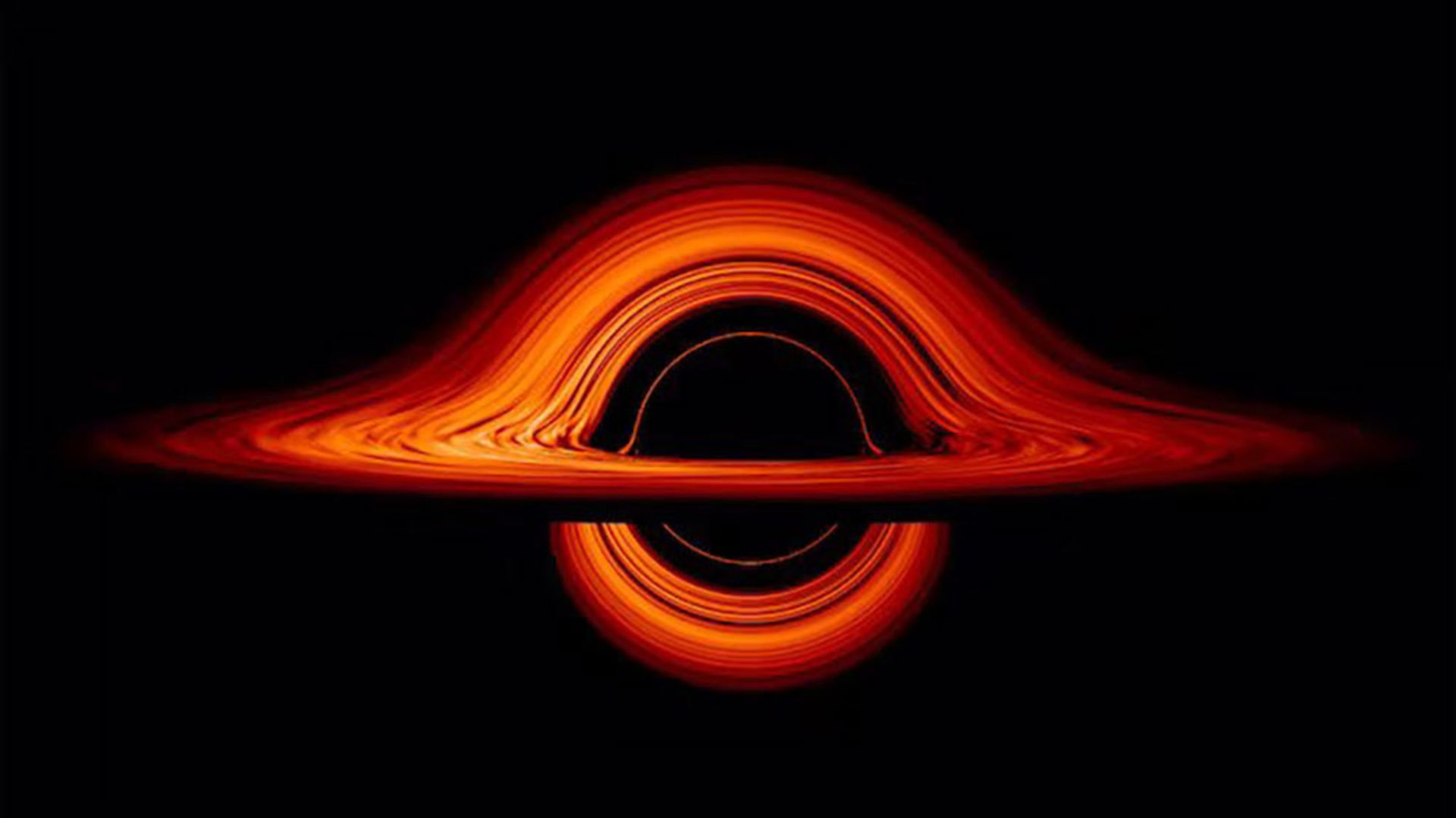

An artist’s rendering of a supermassive black hole complete with a fiery accretion disk.

An artist’s rendering of a supermassive black hole complete with a fiery accretion disk.

By comparing supermassive black holes spanning 9 billion years of the universe’s history, researchers have found a clue that the greedy giant objects at the heart of most galaxies could be the source of dark energy. The articles of this research were published in The Astrophysical Journal and The Astrophysical Journal Letters on February 2 and 15. Chris Pearson, one of the authors of the study and an astrophysicist at the Appleton Rutherford Laboratory (RAL) in the UK says:

If the theory of this research is correct, it could revolutionize the whole of cosmology, because at least we have found a solution to the origin of dark energy, which has puzzled cosmologists and theoretical physicists for more than twenty years.

The theory that black holes can carry something called vacuum energy (an embodiment of dark energy) is not new, and the discussion of its theory actually goes back to the 1960s; But the new research assumes that dark energy (and therefore the mass of black holes) increases over time as the universe expands. Researchers have shown how much of the universe’s dark energy can be attributed to this process. According to the findings, black holes could hold the answer to the total amount of dark energy in the current universe. The result of this puzzle can solve one of the most fundamental problems of modern cosmology.

Rapid expansion

Our universe began with the Big Bang about 13.7 billion years ago. The energy from this explosion of space once caused the universe to expand so rapidly that all the galaxies were moving away from each other at breakneck speed. However, astronomers expected the rate of this expansion to slow down due to the gravitational influence of all the matter in the universe. This attitude toward the world prevailed until the 1990s; That is when the Hubble Space Telescope made a strange discovery. Observations of distant exploding stars have shown that in the past the universe was expanding at a slower rate than it is now.

Therefore, contrary to the previous idea, not only the expansion of the universe has not slowed down due to gravity, but it is increasing and speeding up. This result was very unexpected and astronomers sought to justify it. Thus, it was assumed that “dark energy” pushes objects away from each other with great power. The concept of dark energy was very similar to a cosmic constant proposed by Albert Einstein that opposes gravity and prevents the universe from collapsing but was later rejected.

Stellar explosions

But what exactly is dark energy? The answer to this question seems to lie in another cosmic mystery: black holes. Black holes are usually born when massive stars explode and die. The gravity and pressure in these intense explosions compress a large amount of material into a small space. For example, a star roughly the same mass as the Sun can be compressed into a space of only a few tens of kilometers.

The gravitational pull of a black hole is so strong that even light cannot escape it and everything is attracted to it. At the center of the black hole is a space called singularity, where matter reaches the point of infinite density. The point is that singularities should not exist in nature.

Dark energy explains why the universe is expanding at an accelerating rate.

Dark energy explains why the universe is expanding at an accelerating rate.

Black holes at the center of galaxies are much more massive than black holes from the death of stars. The mass of galactic “massive” black holes can reach millions to billions of times the mass of the Sun. All black holes increase in size by accreting matter and swallowing nearby stars or merging with other black holes; Therefore, we expect these objects to become larger as they age. In the latest paper, researchers investigated the supermassive black holes at the centers of galaxies and found that the mass of these objects has increased over billions of years.

Fundamental revision

The researchers compared the past and present observations of elliptical galaxies that lack the star formation process. These dead galaxies have used up all their fuel, and as a result, their increase in the number of black holes over time cannot be attributed to normal processes that involve the growth of black holes by accreting matter.

Instead, the researchers suggested that these black holes actually carry vacuum energy, which has a direct relationship with the expansion of the universe, so as the universe expands, their mass also increases.

Visualization of a black hole that could play a fundamental role in dark energy.

Visualization of a black hole that could play a fundamental role in dark energy.

Revealing dark energy

Two groups of researchers compared the mass of black holes at the center of two sets of galaxies. They were a young, distant cluster of galaxies with lights originating nine billion years ago, while the closer, older group was only a few million light-years away. Astronomers found that supermassive black holes have grown between seven and twenty times larger than before so this growth cannot be explained simply by swallowing stars or colliding and merging with other black holes.

As a result, it was hypothesized that black holes are probably growing along with the universe, and with a type of hypothetical energy known as dark energy or vacuum that leads to their expansion, they overcome the forces of light absorption and destruction of the stars in their center.

If dark energy is expanding inside the core of black holes, it can solve two long-standing puzzles of Einstein’s general relativity; A theory that shows how gravity affects the universe on massive scales. The new finding firstly proves how the universe does not fall apart due to the overwhelming force of gravity, and secondly, it eliminates the need for singularities (points of infinity where the laws of physics are violated) to describe the workings of the dark heart of black holes.

To confirm their findings, astronomers need more observations of the mass of black holes over time, and at the same time, they need to examine the increase in mass as the universe expands.

Artificial intelligence could explain why we haven’t seen extraterrestrials yet

Samsung Galaxy A55 vs Galaxy A35

Can humans endure the psychological torment of living on Mars?

Xiaomi Pad 6S Pro review

Metaverse is back

One UI 6.1 user interface review; The most complete Android skin

Climate change slows down the rotation of the earth!

Review of Motorola Edge 40 ; Pure Android in a lovely body

Review of Xiaomi 14 Ultra, price and specifications

What would happen if gravity stopped?

Popular

-

Technology9 months ago

Technology9 months agoWho has checked our Whatsapp profile viewed my Whatsapp August 2023

-

Technology10 months ago

Technology10 months agoHow to use ChatGPT on Android and iOS

-

Technology9 months ago

Technology9 months agoSecond WhatsApp , how to install and download dual WhatsApp August 2023

-

Technology10 months ago

Technology10 months agoThe best Android tablets 2023, buying guide

-

Humans1 year ago

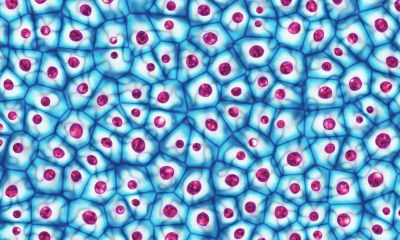

Humans1 year agoCell Rover analyzes the inside of cells without destroying them

-

AI1 year ago

AI1 year agoUber replaces human drivers with robots

-

Technology10 months ago

Technology10 months agoThe best photography cameras 2023, buying guide and price

-

Technology10 months ago

Technology10 months agoHow to prevent automatic download of applications on Samsung phones