Space

Why there is no gaseous moon in solar system?

Published

2 weeks agoon

Why there is no gaseous moon in solar system?

In the solar system, we have rocky moons (such as Earth’s moon ), oceanic moons (such as Europa and Enceladus ), and frozen icy moons (such as Triton), but there are no gaseous moons. Is it because of bad luck that we don’t have gas moons or is there a physical reason for their absence?

Indeed, gaseous moons exist! Although they are not in the solar system. Although more than 5,500 extrasolar planets have been discovered so far, only two possible extrasolar moons have been identified and the existence of none of them has been definitively confirmed yet. The strange thing about these two exosolar moons is that they are gas giants orbiting larger gas giants. Of course, as we shall see, they are the exceptions that prove the rule.

To understand why gas moons do not exist, at least in the solar system, it is better to learn how gas giant planets form.

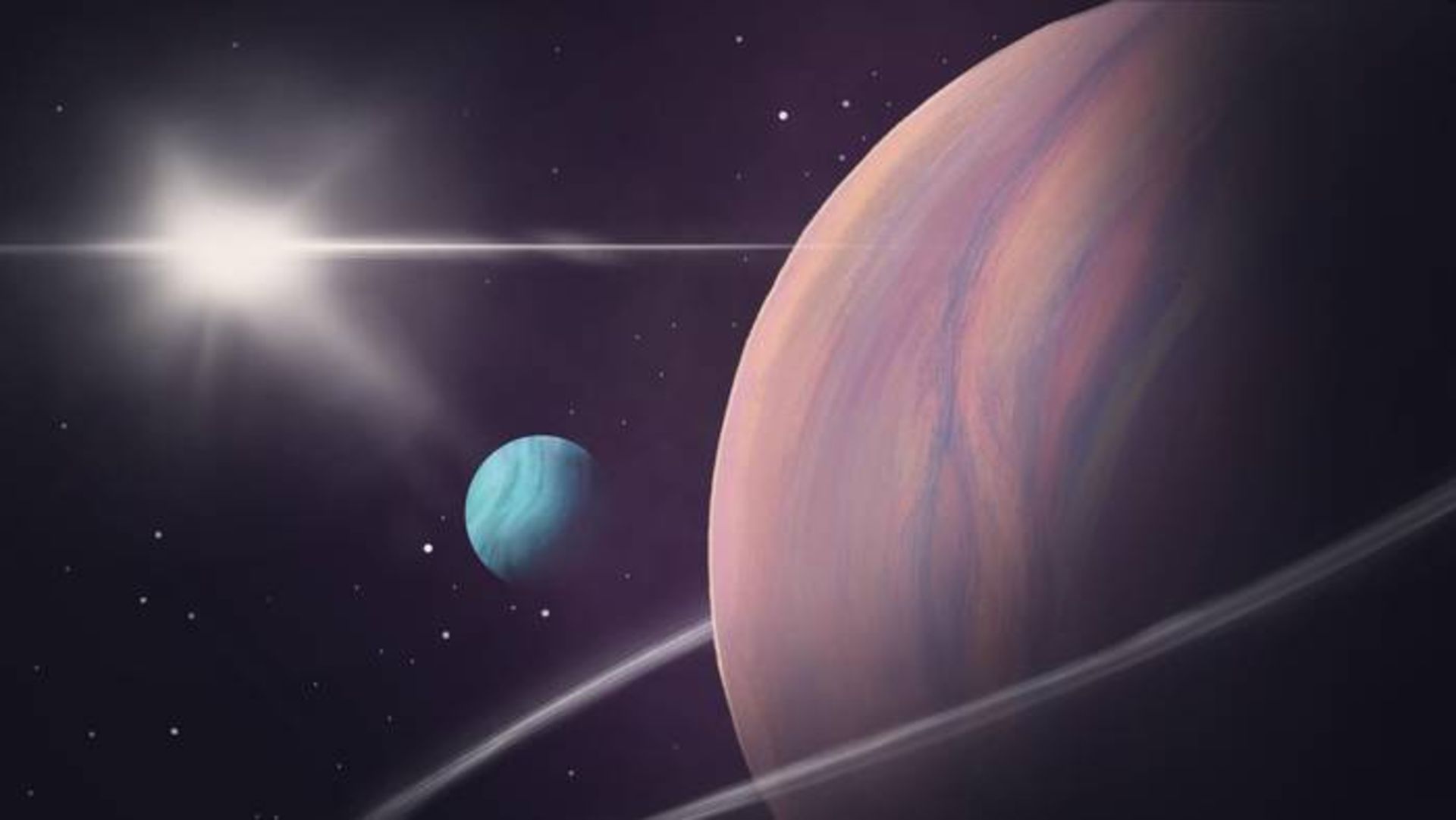

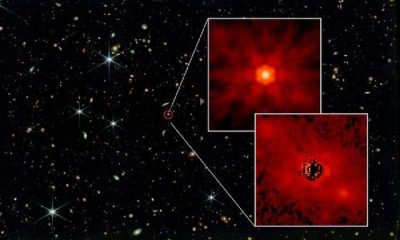

Artist’s impression of Kepler 1625b-i, the possible moon of the exoplanet Kepler 1625b and the star of the system.

Artist’s impression of Kepler 1625b-i, the possible moon of the exoplanet Kepler 1625b and the star of the system.

There are two scenarios for the formation of a gas giant planet: the bottom-up scenario and the top-down scenario.

The formation of gaseous worlds according to the bottom-up scenario

The bottom-up, or “core accretion” scenario, explains how the gas giant planets of the Solar System formed.

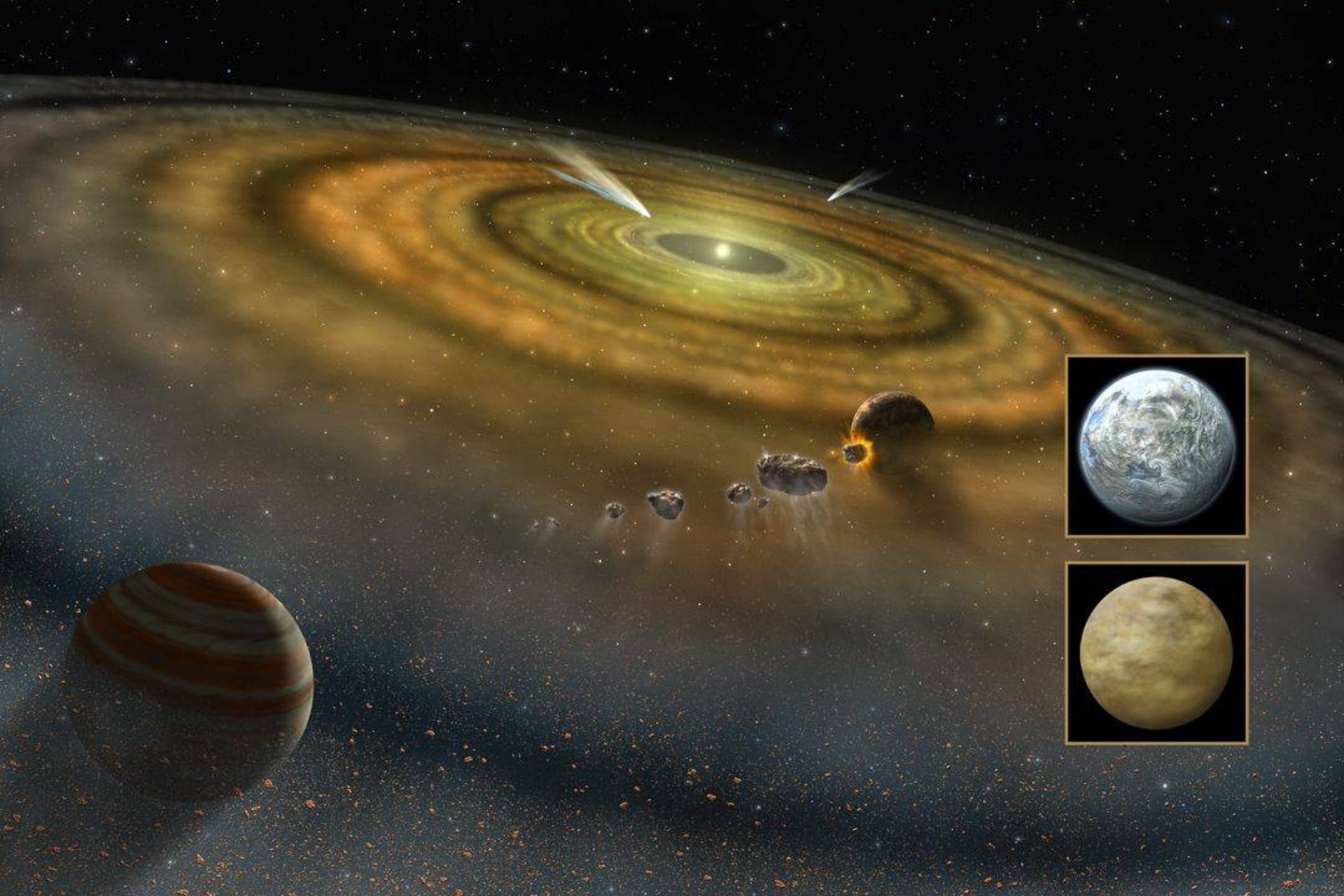

If we could go back 4.5 billion years, we would see a young Sun surrounded by a disk of gas and dust. All planets are formed from this protoplanetary disk. They first formed as rocky bodies and grew larger by collecting dust, pebbles, and surrounding asteroids. Some of them only grew to the size of Mars or Venus, but others continued to grow and became giant rocky bodies with about 10 times the mass of Earth.

When planets grow to such large sizes, their gravity is strong enough to pull huge amounts of gas from the protoplanetary disk. How much gas they stole and how big they grew depended on their gravity and the amount of gas available. But in the end, our solar system was left with four gas-giant planets, Jupiter and Saturn, and the ice giants Uranus and Neptune.

NASA’s Juno mission to Jupiter has detected gravity from a large, rocky, yet diffuse core about ten times the mass of Earth at the center of Jupiter, helping to find evidence for the core accretion model.

The planets of the solar system were formed during the bottom-up process or core accretion in the protoplanetary disk.

The planets of the solar system were formed during the bottom-up process or core accretion in the protoplanetary disk.

The formation of gaseous worlds according to the top-down scenario

In the bottom-up model, gaseous worlds, just like stars, form directly from the disintegrating mass of gas in the nebula. However, there is a minimum amount of mass that can produce this process.

When a large mass of gas contracts under its own gravity, it heats up because the gas is compressed into a smaller and therefore denser volume. But when the gas is hot, it tends to expand, so to maintain the contraction, the mass of gas must remove excess heat. As a result, we often see the collapse of gas clouds that glow as thermal infrared energy.

The radiation of enough heat so that the gas can cool and still decay depends on the dust’s opacity, temperature, and density, and the process becomes more inefficient in smaller objects; So, at a mass about three times that of Jupiter, it cannot generate enough heat to continue disintegrating. The smaller the volume, the cloudier and denser the dust becomes, and the process of radiating the excess heat due to gravitational contraction becomes increasingly inefficient. Therefore, an object smaller than three times the mass of Jupiter cannot form during the top-down process.

Why does the solar system not have a gaseous moon?

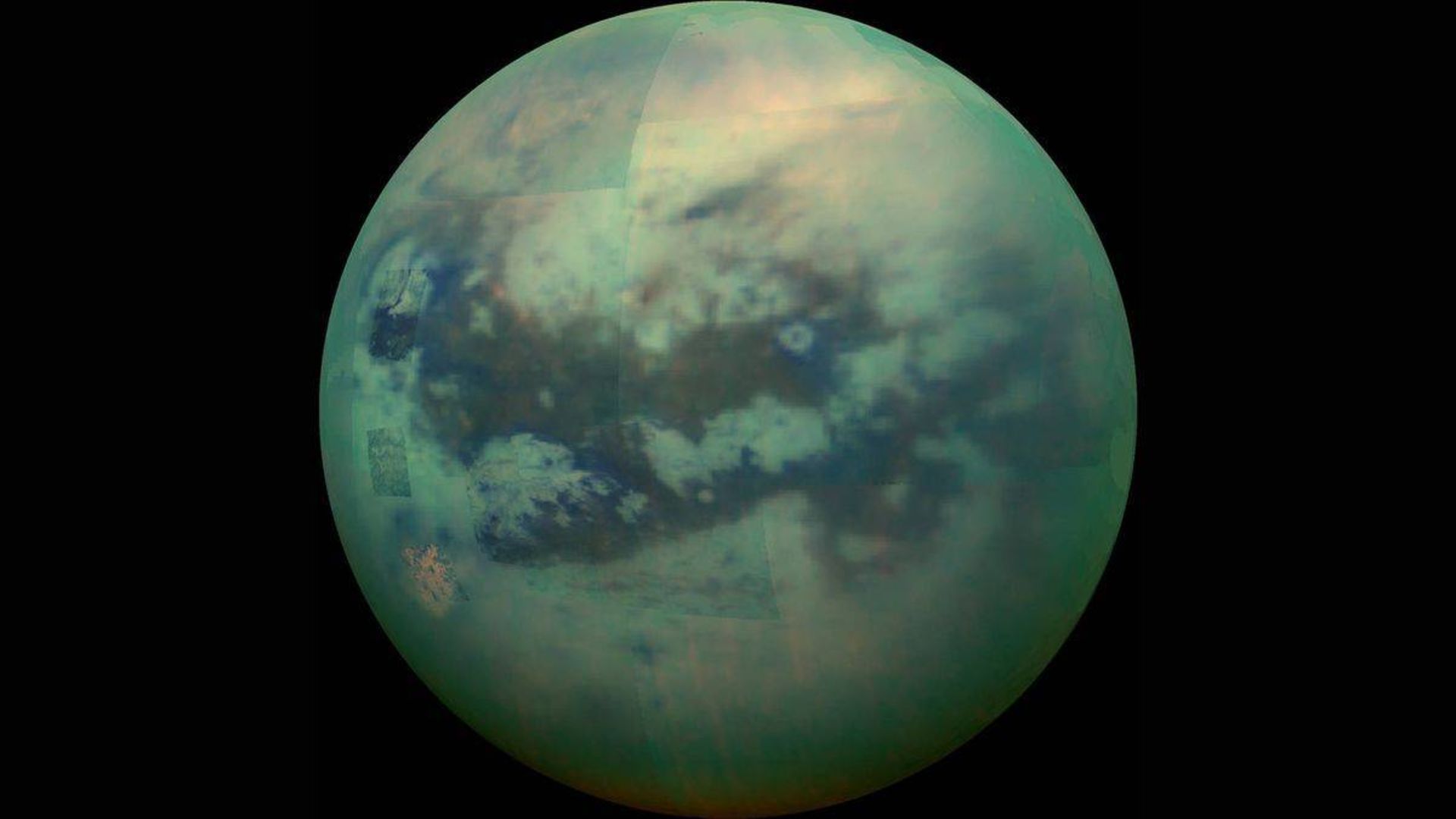

Most of the moons of our solar system, like their parent planets, were formed by the process of core accretion from the bottom up in disks of residual material that surrounded their parent planets. Since the planets had already collected most of the available material, there was not enough material left to form a moon with enough mass to have enough gravity to hold a large amount of gas. In fact, only one moon in the solar system even has an atmosphere, and that is Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. Similarly, the top-down process could not occur because there was not enough gas left.

Titan, Saturn’s moon, is the only moon in the solar system that has an atmosphere.

Titan, Saturn’s moon, is the only moon in the solar system that has an atmosphere.

Strange moons

According to the explanations given, in the solar system, gaseous moons cannot be formed through the two conventional processes of producing gaseous universes. However, there are wonders in our cosmic neighborhood that are formed in a different way.

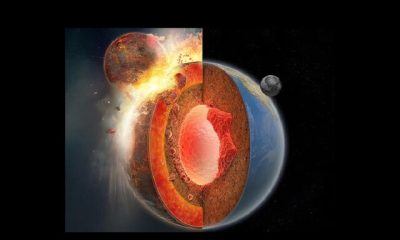

In the case of Earth, the Moon is likely formed from material blasted from Earth following a massive collision with a Mars-sized protoplanet. These remnants formed a ring that created the moon’s core through accretion. But could the impact of a gas giant planet eject enough gas to form a gas moon?

Unfortunately no. Rocky planets can experience such collisions, but remember when Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 hit Jupiter in 1994 and disappeared, Jesse Christiansen of the California Institute of Technology told Space.com. Gas giants devour everything. Anything that hits a gas giant just becomes part of the gas giant instead of throwing debris into space.

Another strange case is the trapped moons. For example, the moons of Mars, Phobos, and Deimos, are trapped by the red planet’s gravity. Saturn’s outermost moon Phoebe is a captured comet mass, and Neptune’s moon Triton is a Kuiper Belt mass that was trapped by Neptune’s gravity millions of years ago. They did not form around the planet, but formed on their own in space and then drifted until they were finally trapped by a planet’s gravity.

Now, the question arises, can a smaller gas planet be captured by a larger gas planet? After all, gaseous worlds can reach up to 12 times the size of Jupiter, so in principle, they could trap a gaseous world the size of Neptune.

Gaseous extrasolar moons

It seems possible for smaller gaseous bodies to be captured by larger gaseous planets. “It’s possible that there are (gas) moons around the size of Neptune around giant exoplanets,” Christiansen said.

The two possible exomoons mentioned at the beginning of the article (Kepler 1625b-i and 1708b-i) are both gas giants in their own right but appear to be originally moons of larger gas giants. “Both of these are candidates,” Christiansen says. “We see something in the data that is consistent with the moon, but other phenomena could also explain it.”

Assuming that Kepler 1625b-i is a real moon, it has a mass 19 times that of Earth (about 6% of the mass of Jupiter), is similar in mass to Neptune, and accompanies a gas planet with a mass 30 times the mass of Earth and a diameter equal to half that of Jupiter. Kepler 1708b-i is probably less massive than Kepler 1625b-i, has a diameter about five times that of Earth (about half the diameter of Kepler 1625b-i), and orbits a gas planet 4.6 times the size of Jupiter.

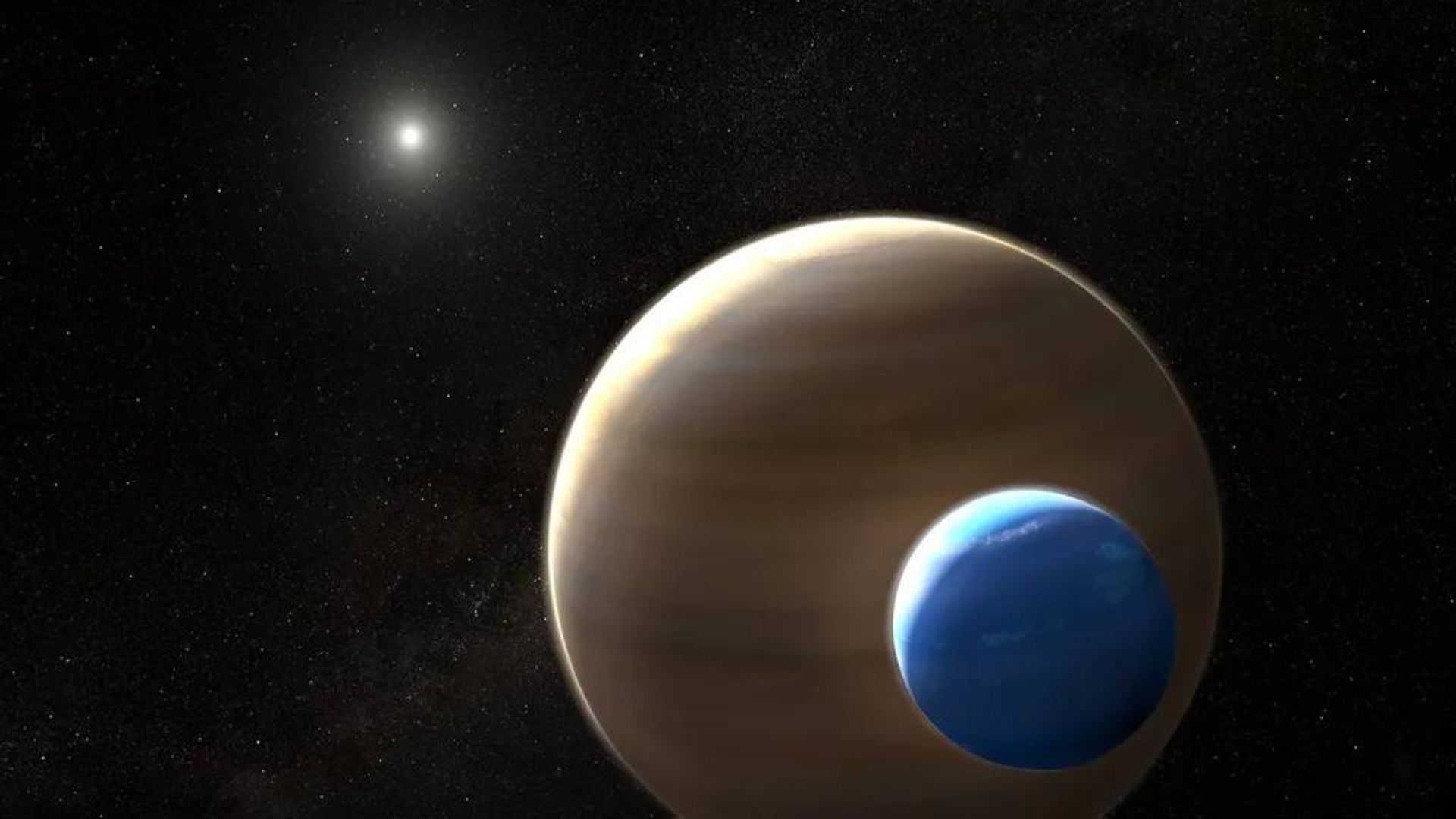

Artist’s impression of an exomoon orbiting the exoplanet Kepler 1708b.

Artist’s impression of an exomoon orbiting the exoplanet Kepler 1708b.

“They challenge a lot of theories,” says Christiansen. “It’s hard to find a way for moons to form, so they must be trapped.” Being trapped makes them virtually like captured moons in the solar system. Like planets, they form from accretion cores in the disk and are then captured as they migrate towards their star.

Migration appears to be a common process in young planetary systems. Migration is the astronomers’ explanation for objects known as “hot Jupiters,” which are gas giants very close to their star but may have originally formed further away.

The extrasolar moons Kepler 1625b-i and Kepler 1708b-i were captured by larger planets as they migrated in front of them. However, they are probably not true moons, but rather examples of binary planets rather than extrasolar moons.

A binary planet exists when both worlds orbit the center of mass between them, rather than one orbiting the other. In our solar system, we have a double planet in the form of Pluto and its largest companion, Charon.

So, gas moons exist somehow, but nature has to cheat to make them!

You may like

-

History of the world; From the Big Bang to the creation of the planet Earth

-

A mystery that is solved by the China’s Chang’e-6 probe!

-

Discover a new answer to the ancient mystery of a Venus!

-

Discovering new evidence of the impact that formed the Earth’s moon

-

Maybe alien life is hidden in the rings of Saturn or Jupiter

-

Discovering new clues about the formation of the world’s first black holes

Space

History of the world; From the Big Bang to the creation of the planet Earth

Published

10 hours agoon

13/05/2024

History of the world; From the Big Bang to the creation of the planet Earth

Since its launch in 2021, the James Webb Space Telescope has sent us spectacular images of the universe’s deep field. This telescope revealed fine details like a galaxy with an age of 13.1 billion. Such distant objects may not be visually impressive, appearing as fuzzy red blobs in images, but they can provide a fascinating glimpse into the universe’s infancy.

Space and time are intertwined. Light travels at a constant speed, so the images captured by telescopes like James Webb’s are actually images of the universe from millions or even billions of years ago. The higher the sensitivity and accuracy of a telescope, the more distant objects it can observe and thus display more distant times. As the most powerful telescope ever launched, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is extremely sensitive. This telescope can theoretically see objects within 100 million years since the formation of the universe.

-

The first moments

-

Initial plasma

-

The world becomes transparent

-

Cosmic Dark Age

-

The first habitable age

-

The first lights in the dark

-

Blooming cosmos with stars

-

Star seeds

-

The oldest known star

-

The oldest known planet

-

The formation of galaxies

-

Large-scale structures of the universe

-

Collision of galaxies

-

Massive black holes

-

The formation of the Milky Way disc

-

Overcoming dark energy

-

The birth of the sun

-

The formation of the earth

-

The first forms of life

-

Extraterrestrial life and alien civilizations

There are still many unknowns about the history of the universe, but telescopes like Webb’s can unravel these mysteries and reveal unprecedented detail.

History of the world

The first moments

The universe was born about 13.8 billion years ago from the Big Bang.

The universe was born about 13.8 billion years ago from the Big Bang.

The entire universe was created from an ancient and vast explosion that continues to this day. This spark , called the Big Bang, happened nearly 13.8 billion years ago. The Big Bang is the best hypothesis ever proposed for the existence of the universe. Although there is still no way to directly observe the Big Bang, this theory is well established and has been confirmed by many scientists over the past few decades.

In the first moments of the universe, a fraction of a second after the Big Bang, everything was inside a singularity, which is an infinitesimally small point of space with a very strange and high density that encompasses everything. In a few moments after the birth of the universe, the world was in an era known as Planck’s age. In this era, the whole world was so small that space and time had no meaning. Then, in less than a second, the universe entered a phase known as cosmic inflation, and for a moment, it expanded greatly. The infant universe consisted of a hot soup of subatomic particles and radiation, preventing any kind of structure from forming.

Initial plasma

The universe was initially filled with turbid, hot plasma.

The universe was initially filled with turbid, hot plasma.

The early universe was a highly viscous place filled with turbid plasma for several thousand years. This murky plasma was a mass of subatomic particles that were too hot to contract into atoms. The lack of transparency of the early world makes it impossible to see the events of that time; However, the early chapters of the universe’s history are of interest to many cosmologists because they represent a stage for the existence of everything.

Scientists believe that the early universe was filled with equal amounts of matter and antimatter, which eventually annihilated each other, leaving only a small amount of matter in the present universe. The question of why one of them was more remains a mystery and physicists are still trying to answer this question.

Eventually, the universe cooled and atoms and then strange molecules began to form. The first molecule that was formed in the world was made of only two elements, hydrogen and helium. These molecules finally made a compound called helium hydride. This chemical reaction actually created a helium compound that looks like it shouldn’t exist.

The world becomes transparent

The world became transparent after 300 thousand years.

The world became transparent after 300 thousand years.

On its 300,000 birthday, the world entered an era known as the age of recombination. It was during this period that atoms began to form, although the word “recombination” is a bit of a misnomer because it was during this period that everything was combined together for the first time. As the universe cooled enough, matter began to form atoms, and the universe became transparent for the first time. This transparency allowed the light left over from the Big Bang to spread throughout the universe.

The ancient Big Bang radiation marks the edge of the visible universe and can still be observed. As the universe continues to expand, the light in it is stretched, which astronomers witness in the form of the redshift phenomenon. The older the light of an object, the more it is stretched and moves to the red side of the spectrum like infrared and finally to longer wavelengths.

The initial light of the birth of the world is the most stretched light and the human eye cannot observe it. This light can be seen in all directions today as the cosmic background radiation (CMB). As seen in the image above, some speckled areas show slight fluctuations left over from cosmic inflation. These faint background rays are the last reflections of the birth of the universe.

Cosmic Dark Age

The world had no stars in the dark ages.

The world had no stars in the dark ages.

With the universe filled with atoms, light was finally able to move freely in open space. However, there was nothing in the universe capable of producing light. In fact, this age of the world is known as the age of cosmic darkness. In this period, the stars were not yet born and the space was full of silence and infinite darkness. The universe was in its infancy and there was nothing but dark matter with neutral helium and hydrogen, But it was in this darkness that the materials of the world gradually joined each other.

Finally, with the formation of the first stars, the world entered an era known as the Bazion, and the first stars shone. They emitted intense ultraviolet light in the dark and eventually removed the electrons from the new atoms; But even though the stars were shining for the first time in the universe, their light could not travel very far. Because the entire space was filled with a fog of hydrogen gas and blocked the light of the first stars. After some time, the starlight traveled further distances and reached us today.

The first habitable age

According to calculations, the first habitable age started in 10-17 million years of the world.

According to calculations, the first habitable age started in 10-17 million years of the world.

According to human earth standards, any place with liquid water can be classified as habitable. As the early Earth cooled, the surprising truth was revealed that the entire universe was once at a habitable temperature. According to an article published in the International Journal of Astrophysics, this period is called the early habitable age. Based on this hypothesis, the question arises as to what exactly happened in a world where life theoretically existed everywhere. According to calculations, this cosmic age corresponds to the time when the universe was still 10 to 17 million years old.

Of course, scientists have differences in this hypothesis. According to an article in Nature that argues against this idea, life requires a hot-to-cold energy flow and cannot exist in a uniformly warm universe. Furthermore, at this early age it is not known whether the universe had stars or planets, or even oxygen to produce water. However, this hypothesis cannot be completely rejected. The first planets were probably formed in the first few billion years of the universe; So the hypothesis of an early habitable age is little more than a fascinating thought experiment.

History of the world

The first lights in the dark

The first stars of the universe were composed of light elements.

The first stars of the universe were composed of light elements.

The first stars of the universe were formed from the virgin material left over from the Big Bang and were the cause of the formation of the first heavy elements of the universe. These stars, which lacked elements heavier than helium, are known as population 3 stars (confusingly named stellar populations in the wrong order). Since these stars were responsible for the formation of the heavy elements of the universe, they must have existed at some point in history. These objects are expected to have formed between 100 million and 250 million years after the Big Bang.

According to the models, Population 3 stars were very massive and short-lived by today’s stellar standards. The lifetime of some of these stars reached only 2 million years, which is a long time from the human point of view; But on a stellar scale, it’s like a blink of an eye. When these stars ended their lives, they likely perished in unstable binary supernova explosions, the most violent type of stellar explosion in the universe. Although no stars belonging to this group have been observed so far, perhaps this trend will change with powerful instruments such as the James Webb Space Telescope.

Blooming cosmos with stars

Some stars of the Milky Way date back to 11 to 13 billion years ago.

Some stars of the Milky Way date back to 11 to 13 billion years ago.

We live in a season of the world known as the age of star formation. This age is the beginning of the stars shining in the dark and is actually the modern age of the world, in which the cosmic matter turns into stars, planets and galaxies. According to scientists, the era of star formation began approximately one million years after the Big Bang and will continue until the universe is 100 trillion years old. Until the very distant future, the birth, life and death of stars in the universe and the fusion of hydrogen into heavier elements will continue until hydrogen disappears completely.

Although stars are actively forming in the universe, there is a wide range from newly born stars to very old stars. Stars can live for billions of years. Red dwarfs, the smallest and most populous stars in the universe, live so long that their deaths have not been recorded until now because the universe is not old enough. Astronomers have also observed very old stars in the universe, some of which date back to the earliest days of the Milky Way, between 11 and 13 billion years ago. Stars like this have been observed for most of the history of the universe.

Star seeds

Nebulae are breeding grounds for the formation of new stars

Nebulae are breeding grounds for the formation of new stars

By weight, most of Earth is made up of chemical elements heavier than helium, which are made in the cores of stars. This process is known as nucleation. During the lifetime of a star, nuclear reactions combine light elements and produce heavier elements. In this way, elements such as carbon, oxygen, silicon, sulfur and iron are formed in the hearts of stars. When stars run out of fuel, they throw the elements they made back into the universe.

Stars fill the galaxy with elements by their birth and death over billions of years. Carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen are among the most abundant elements made by smaller stars. As these stars die, their outer layers form a stellar nebula. From this example, we can refer to the Southern Ring Nebula, whose image was published by the James Webb telescope.

The life of the biggest stars also ends in a supernova explosion. These explosions not only fill galaxies with heavy elements such as iron, but their shock waves can be the basis for the birth of new stars.

History of the world

The oldest known star

The oldest star in the universe was formed only 100 million years after the Big Bang

The oldest star in the universe was formed only 100 million years after the Big Bang

The hunt for the oldest stars in the universe is one of the fascinating fields of astronomy that can help scientists understand the early days of the universe. The oldest star ever discovered is HD 140283. The star is so old that the first estimates of its age are older than the universe itself. However, this effect is an illusion caused by the uncertainty in the estimates. Therefore, measuring the age of a star is not an easy task.

According to another research in the Journal of Astronomy and Astrophysics, the age of HD 140283 was estimated to be almost the same as the age of the universe, i.e. 13.7 billion years. In other words, this star was probably born a hundred million years after the Big Bang, and thus it is one of the first generation of stars that were born in the world. This star is metal-poor, or in other words, has a small number of chemical elements heavier than helium, and thus it is placed in the category of population 2 stars. Such stars are among the oldest objects that have ever shone in the universe. Based on the ratio of chemical elements, these stars are survivors of early stars from the early days of the universe.

The oldest known planet

The oldest planet in the world is nearly 12.7 billion years old.

The oldest planet in the world is nearly 12.7 billion years old.

No one knows exactly when the first planets formed, but they seem to be able to outlive stars. The oldest known planet orbits two dead stars, one of which is a pulsar and the other a white dwarf. Both stars are stellar wrecks that have run out of fuel and have released much of their chemical material into their galaxy. The mentioned pulsar is called PSR B1620 and the planet located in its orbit is known by the nickname Methuselah. This planet, which is a kind of gas giant, is not unlike the planet Jupiter.

According to estimates, the lifespan of Methuselah reaches 12.7 billion years, but this age is not exact. There is no good way to estimate the age of planets, so this estimate is based on other stars in the Methuselah cluster. Globular clusters, such as the Methuselah host cluster, are full of stars that formed at the same time.

According to the research of Science magazine, the existence of the ancient planet Methuselah offers interesting hints about the time of formation of the oldest planets. If the estimates are correct and Methuselah is really 12.7 billion years old, we can say that the planets were formed earlier than we think. In other words, Methuselah may not be the only ancient planet in our galaxy.

The formation of galaxies

Galaxies usually come together in several clusters

Galaxies usually come together in several clusters

When the universe was only 200 million years old, the first galaxies were formed. The discovery initially surprised astronomers because they thought galaxies formed much later. Early galaxies were not similar to today’s massive galaxies. Rather, they were shapeless clouds of irregular gas and dust. These galaxies, accompanied by a wave of star birth, eventually became the massive galaxies that fill the universe today. It seems that the Milky Way galaxy was formed approximately 13.6 billion years ago. Our galaxy was then an unrecognizable mass of stars, not unlike the present spiral.

The oldest galaxy ever discovered was formed 300 million years after the Big Bang. This galaxy is called HD1 and the James Webb telescope played an important role in determining its age. HD1, if confirmed, would be the oldest galaxy ever seen by astronomers and could offer fascinating insights into the formation of the universe’s first galaxies. The formation of galaxies is still a mysterious research field full of unanswered questions. Helping to solve these questions will be one of the main goals of the James Webb telescope.

Large-scale structures of the universe

Galaxies are held together by gravity and form large-scale cosmic structures

Galaxies are held together by gravity and form large-scale cosmic structures

Much of the world seems to be an empty void, But the universe has complex structures on very large scales. The universe is covered with an array of dark matter filaments that form a web-like structure. This network of dark matter, called large-scale structure, shapes the universe and causes galaxies to fall into regular patterns. The gravity of the large-scale structure causes both dark and visible matter to lie next to each other. By examining this structure, we can find signs of the youth of the world.

Deep background images, such as the James Webb Telescope image, can reveal how galaxies fit together. These structures are actually the largest visible structures or galaxy strings in the universe, held together by gravity. In addition, the structures are not random but have an order that still fascinates researchers. Galaxies and large galaxy clusters appear to be evenly spaced in the galactic strings, resembling a pearl necklace. There are still many uncertainties about large-scale structures.

Collision of galaxies

Some galaxies collide and form larger galaxies.

Some galaxies collide and form larger galaxies.

Gravity pulls everything in the universe together, and the heavier the mass, the greater this attraction. Galaxies are among the heaviest objects in the universe, whose formation and evolution are still a matter of discussion and their evolution is strongly influenced by their interaction with each other.

Galaxies usually tend to form groups or clusters that come together due to gravity and start interacting when they are close to each other. The gravitational pull of galaxies leads to the creation of lethal forces. In the most dramatic examples, galaxies can collide and their merger may take billions of years.

Galactic collisions can lead to the formation of new stars; Because the change of gravitational forces causes disturbances on huge scales. Some stars are ejected into the dark intergalactic space, while others are trapped by the gravity of supermassive black holes at the center of colliding galaxies. As the galaxies merge, their spiral arms are eventually destroyed, and the two galaxies eventually become one massive elliptical galaxy. In this way, some of the largest galaxies in the universe are formed. Some galaxies also grow by absorbing smaller galaxies. According to some evidence, the Milky Way has experienced such a collision in the past, and its signs can be seen in the form of remnants of galaxies that it has absorbed in the past.

History of the world

Massive black holes

Quasars are caused by the feeding of the black hole from the surrounding matter.

Quasars are caused by the feeding of the black hole from the surrounding matter.

The largest galaxies, such as the Milky Way, have a supermassive black hole at their center; Although how these black holes formed is still a mystery, it is clear that they are very old. The European Space Agency has released an image of an ancient galaxy known as UDFj-39546284, which appears to be a small red dot in the image. This spot is actually the oldest quasar observed by astronomers and dates back to 380 million years after the Big Bang.

Quasars are among the brightest objects in the world, which are created by the feeding of the supermassive black hole at the center of a galaxy from the surrounding material. The big question here is how these black holes have reached these dimensions at a high speed. According to a study published in the journal Nature, supermassive black holes appear to have formed suddenly from turbulent cold gas in the early universe. In the right conditions, black holes were formed with great intensity and suddenly as a result of the collapse of streams of initial materials grew to dimensions exceeding 40,000 times the mass of the Sun.

The formation of the Milky Way disc

In the first 3 billion years of its existence, the Milky Way had no spiral arm.

In the first 3 billion years of its existence, the Milky Way had no spiral arm.

Today, the Milky Way is a spiral galaxy, but it hasn’t always been this way. The spiral galaxy formed in a galactic disk, but the Milky Way disk formed about ten billion years ago. This means that our galaxy spent its first three billion years without a disk and therefore had no spiral arm.

The disk of a spiral galaxy contains a large part of the material of that galaxy. In such galaxies, star birth often occurs in spiral arms, as stars are formed from vast clouds of gas and dust slowly swirling around the galactic core. How and why spiral arms and disks are formed is still not completely clear, although this phenomenon has been observed frequently in the sky.

Some galactic disks appear to be very old. The oldest galactic disk ever seen is the Wolf disk. This old spiral galaxy dates back to when the universe was only 1.5 billion years old. Of course, due to the distance of this galaxy, we have no information about its new appearance.

Overcoming dark energy

Mysterious dark energy is responsible for accelerating the expansion of the universe.

Mysterious dark energy is responsible for accelerating the expansion of the universe.

One of the milestones in world history can be related to dark energy; The mysterious force that controls the expansion of the universe. No one knows exactly what dark energy is, although astronomers can measure its effects. Until a long time ago, the universe was in a tug-of-war between the force of gravity and the repulsive force of dark energy. At some point around 5-6 billion years ago, dark energy won the race. As the universe continued to expand, dark energy overcame gravity and accelerated the expansion of the universe.

The effect of dark energy on the future of the universe is still unclear. Without knowing more about dark energy or how it works, there’s no way to know. Although dark energy appears to make up a large part of the universe, its specifics are still shrouded in mystery. According to a possibility, this energy can be one of the inherent characteristics of space itself.

The birth of the sun

The sun was formed about 4.6 billion years ago from a cloud of gas and dust.

The sun was formed about 4.6 billion years ago from a cloud of gas and dust.

The sun is almost a third of the entire universe. This star was formed about 4.6 billion years ago. With the formation of the sun, the clouds of gas and dust around it formed planets such as Earth and many moons of the solar system.

The sun is one of the population’s 1 stars. Such stars are among the newest stars in the universe and are rich in heavy elements, examples of which can be found on Earth. According to a hypothesis, the shock wave resulting from a supernova was the cause of the formation of the solar system from vast dust clouds. The traces of this supernova exist in the form of radioactive isotopes in the entire solar system; So a star died so we could live.

The formation of the earth

Earth was formed from the joining of asteroids.

Earth was formed from the joining of asteroids.

According to scientists, the story of the formation of the earth goes back to 4.6 billion years ago. Our planet formed in a disk-like cloud of gas and dust around the primordial Sun. Inside this disk, gas and dust particles of different sizes were rotating at different speeds in the orbit of the sun and in this way, they collided and stuck to each other. Finally, the tiny particles turned into huge rock fragments and objects called asteroids, whose diameters ranged from one to hundreds of kilometers.

Asteroids eventually gained enough gravity to clear their orbits and attract other bodies through collisions, becoming larger bodies several thousand kilometers in diameter and forming planets.

The first forms of life

The first life on earth dates back to 3.7 billion years ago.

The first life on earth dates back to 3.7 billion years ago.

Life on Earth is the only life we know of in the entire universe. Life first appeared about 3.7 billion years ago, shortly after the formation of the Earth itself. Thus known life is roughly a quarter of the age of the universe, although the complex life that would eventually become humans is much more recent.

Carbon is an essential element for life and appears to have been unavailable until 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang. For this reason, it is still not possible to estimate with certainty the first form of life in the entire universe. Maybe other parts of the world have different chemistry or different elements than life on Earth.

Extraterrestrial life and alien civilizations

Life in other parts of the world may be chemically different from life on Earth.

Life in other parts of the world may be chemically different from life on Earth.

To quote the late astronomer Carl Sagan, “We are a way of knowing the world.” Humans are part of the world like the most distant stars or galaxies. In other words, at least a part of the world is capable of thinking and observing other parts. The oldest early humans appeared on earth approximately 2.4 million years ago; This means that humans and our direct ancestors only existed in 0.02% of the entire history of the world. On a cosmic scale, it seems like we were born just yesterday. However, humans may not be the only civilization in the world.

The question about the existence of other civilizations in the galaxy has a long history. Half of all Sun-like stars could host habitable universes; Therefore, there is no shortage for the formation of civilizations. According to a relatively conservative study, there should be at least 36 space civilizations capable of communicating in the Milky Way. According to another research, there are more than 42 thousand civilizations in the Milky Way. Currently, there is no way to find out the existence of these civilizations. With more accurate telescopes, we may be able to find evidence that we are not alone in this infinite universe.

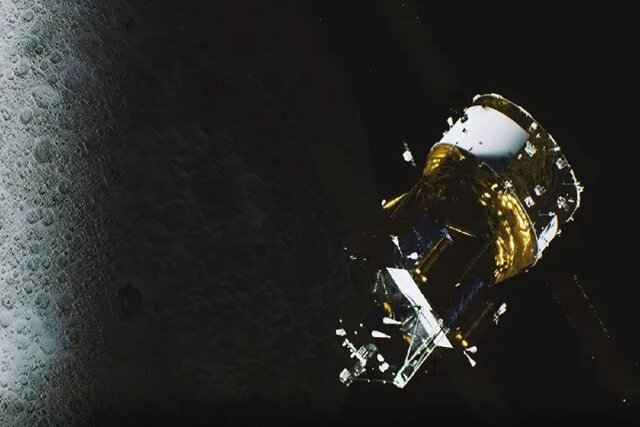

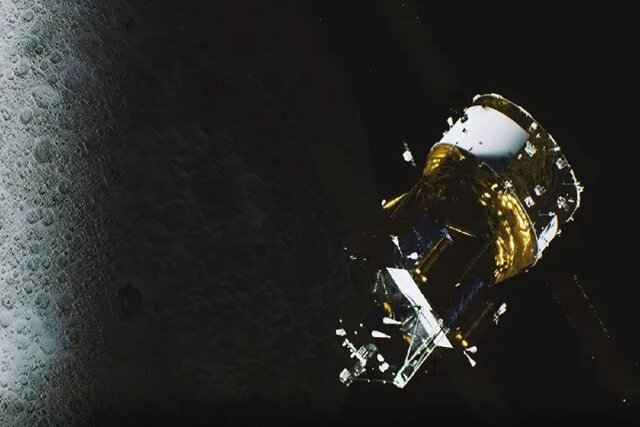

China’s Chang’e-6 probe, launched to retrieve samples from the far side of the moon, has a big mystery to solve about Earth’s moon.

A mystery that is solved by the China’s Chang’e-6 probe!

China’s Chang’e-6 mission, which is currently on its way to bring back samples from the far side of the moon, will help investigate theories about why the far and near sides of the moon differ.

According to Space, Changi 6 is expected to land in early June in the Apollo impact basin, which is located within the larger South Pole–Aitken basin.

The Aitken Antarctic Basin is the largest collisional feature of its kind in the solar system, with an area of 2,400 x 2,050 km. This basin was formed about 4.3 billion years ago, which is very early in the history of the solar system.

Although the Apollo Basin is younger, it is the largest impact site within the Aitken Antarctic Basin. Apollo has a two-ring structure, the inner ring consists of mountain peaks with a diameter of 247 km, and the outer ring is about 492 km wide.

The Chang’e-6 mission was launched on May 3 from the Wenchang Satellite Launch Center in Hainan Province, located in southern China, and went to the moon on a Long March 5 rocket.

As the first mission to bring samples from the far side of the moon, Changi 6 is supposed to bring back about two kilograms of precious lunar material. The far side of the moon is a relatively unknown place. The fact that we can’t see the far side of the moon from Earth adds to its mystery. For the first time, the Soviet Union’s “Luna 3” spacecraft photographed the far side of the moon in 1959.

With that photo, scientists around the world were amazed to see how different the far side of the moon is from the side we are familiar with. Although both the far and near sides have many craters, the near side also contains vast volcanic plains called “lunar maria” that cover about 31% of it.

The far side of the moon is opposite and volcanic plains cover only about 1% of it.

So how did the far side and the near side become so different? It seems that the thickness of the shell is one of the factors. In fact, NASA’s GRAIL mission found in 2011 that the far-side crust is on average 20 kilometers thicker than the near-side crust.

The reason for this is thought to be that our moon was formed from debris from the impact of a Mars-sized planet on Earth about 4.5 billion years ago. As the Moon formed from that debris, it became tidally locked. This means that it always shows the face of our planet.

The surface of the earth was completely melted by that big impact and it radiated heat towards the near side of the moon and kept itself molten for a longer time. Scientists believe that the rock vaporizes on the near side and condenses on the colder side, thickening the crust on the far side.

Hong Kong University (HKU) researcher Yuqi Qian is one of the lead researchers on a new project that shows that a sample to be returned to Earth by Chang’e 6 could test this theory. Keyan said: Basic findings show that the difference in crustal thickness between the near and far sides may be the main cause of the difference in the moon’s volcanism.

In places like most distant parts where the Moon’s crust is thick, magma can’t seep through fractures to the surface. In areas such as the near side where the crust is thin, fractures can allow magma to seep in and lead to lava eruptions.

The Aitken and Apollo Antarctic Basins, despite both being on the far side of the Moon, create contradictions. That’s because they’ve gouged deeply into the Moon’s crust, and at the base of these giant impact sites, the crust is thinner than elsewhere on the far side. Volcanic plains also exist within these basins, but only five percent of their area is covered by basalt lava. This limited amount of volcanism seems to contradict the conventional idea that crustal thickness dictates volcanic activity. This creates a paradox in lunar science that has been known for a long time.

An alternative possibility suggests that the near side could contain more radioactive elements than the far side. These elements may have generated heat and led to the melting of the lower mantle. As a result, much more magma has formed and a thinner crust has formed on the near side. Hence, the volcano is more in this area.

However, by landing on one of the few volcanic plains on the far side, Chang’e 6 could provide samples to directly test such theories. In particular, the Apollo Basin area where Chang’e 6 will land contains a variety of materials that require investigation.

Some evidence shows that there were two major volcanic eruptions in this area. Scientists believe that one of them covered the entire region in magma containing a small amount of titanium around 3.35 billion years ago. The other, which probably occurred 3.07 billion years ago, probably contained titanium-rich magma and erupted near the Chaffee S crater. Thus, the thickness is reduced.

Read more: Discovering new evidence of the impact that formed the Earth’s moon

New research shows that bringing samples from near the Chafi S crater will bring the most scientific benefits. This area has titanium-rich basalt in the upper part, titanium-free basalt in the lower part, and various pieces of projectile material from the impact.

“Joseph Michalski” (Joseph Michalski), a researcher at the University of Hong Kong and one of the researchers of this project said: “Diverse sample sources provide important information to answer a set of scientific questions about the Moon and the Apollo Basin.”

These diverse samples can also provide scientists with information about magmatic processes occurring on the far side of the moon. By comparing them with nearby samples brought back to Earth by the Apollo missions, scientists may be able to answer the question of why the number of volcanoes on the far side of the Moon is so limited.

This research was published in the journal “Earth and Planetary Science Letters”.

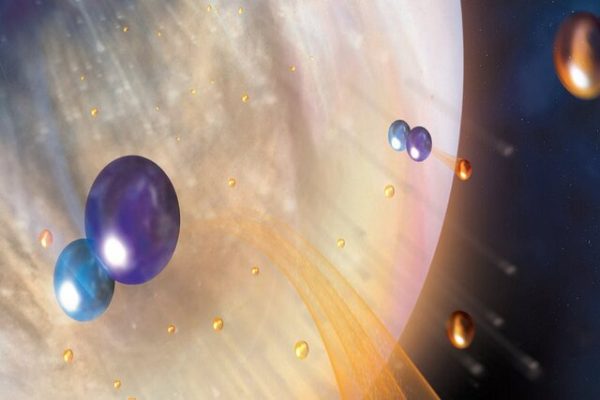

New research from the University of Colorado Boulder shows that Venus is losing water faster than previously thought, which could provide information about the planet’s early habitability.

Discover a new answer to the ancient mystery of Venus!

Today, the atmosphere of Venus is as hot as an oven and drier than the driest desert on Earth, but our neighboring planet was not always like this.

According to Converse, billions of years ago, Venus had as much water as Earth today. If that water was once liquid, then Venus was probably once habitable.

Over time, almost all of Venus’s water reserves have been lost. Understanding how, when, and why Venus lost its water reserves will help planetary scientists understand what makes a planet habitable, or what can turn a habitable planet into an uninhabitable one.

Scientists have theories to explain why most of the water supplies have disappeared, but the amount of water that has disappeared is actually greater than predicted.

Research conducted at the University of Colorado Boulder (CU Boulder) reports the discovery of a new water removal process that has been overlooked in recent decades but could explain the mystery of water loss.

Energy balance and premature water loss

The solar system has a habitable zone. This region is a narrow ring around the Sun where planets can have liquid water on their surface. Earth is in the middle of the habitable zone, Mars is outside on the very cold side, and Venus is outside on the very hot side. The place of a planet in this habitable spectrum depends on the amount of energy received by the planet from the sun and also the amount of energy emitted by the planet.

The theory of how Venus loses water reserves is related to this energy balance. Sunlight on early Venus decomposed the water in its atmosphere into hydrogen and oxygen. Hydrogen warms a planet’s atmosphere, acting like having too many blankets on the bed in the summer.

When the planet gets too hot, it throws the blanket away. Hydrogen escapes into space in a process called “hydrodynamic escape”. This process removed one of the key elements, water, from Venus. It is not known exactly when this process occurred, but it was probably around the first billion years of Venus’ life.

Hydrodynamic volatilization stopped after most of the hydrogen was removed, but some hydrogen remained. This process is like pouring out the water in the bottle, after which there are still a few drops left in the bottle. The remaining droplets cannot escape in the same way, but there must be another process on Venus that continues to remove the hydrogen.

Small reactions and big differences

This new research suggests that a neglected chemical reaction in Venus’s atmosphere could produce enough volatile hydrogen to close the gap between the missing water supply and the observed water supply.

The way this chemical reaction works is in the research of the University of Colorado Boulder. In the atmosphere, HCO ⁺ gas molecules, which are composed of hydrogen, carbon, and oxygen atoms and have a positive charge, combine with negatively charged electrons.

When ⁺ HCO and electrons react, ⁺ HCO breaks down into a neutral carbon monoxide molecule, CO, and a hydrogen atom. This process gives the hydrogen atom the energy it needs to exceed the planet’s speed and escape into space. The whole reaction is called HCO ⁺ dissociative recombination, but the researchers abbreviated it as DR.

Water is the main source of hydrogen on Venus. Thus, the DR reaction dries out the planet. The DR reaction probably happened throughout the history of Venus, and this research shows that it probably continues to this day. This reaction doubles the rate of hydrogen escape previously calculated by planetary scientists, changing their understanding of current hydrogen escape on Venus.

Understanding the conditions of the planet Venus with data and computer models

Researchers in this project used computer modeling and data analysis to study DR in Venus.

Modeling actually began as Project Mars. Mars also had water before – though less than Venus – and lost most of it.

To understand the escape of hydrogen from Mars, the researchers created a computational model of the Martian atmosphere that simulated the chemistry of the Martian atmosphere. Despite being very different planets, Mars and Venus have similar atmospheres. Therefore, the researchers were able to use this model for Venus as well.

They found that the DR reaction produced large amounts of fugitive hydrogen in the atmospheres of both planets. This result is consistent with observations made by the Mars Atmospheric and Volatile Evolution Mission (MAVEN) orbiting Mars.

Collecting data in the Venus atmosphere would be valuable to support the computer model, but previous missions to Venus have not measured ⁺ HCO; Not because it doesn’t exist, but because they weren’t designed to detect it. However, they investigated the reactants that produce HCO ⁺ in Venus’s atmosphere.

By analyzing observations made by the Pioneer probe and using their knowledge of the planet’s chemistry, the researchers showed that ⁺ HCO is likely present in the atmosphere in similar amounts to the computer model.

Searching for water

This research has solved part of the puzzle of how planetary water reserves are lost, which affects how habitable a planet is. We have learned that water loss occurs not only in one moment but over time and through a combination of methods.

Read more: Maybe alien life is hidden in the rings of Saturn or Jupiter

The faster loss of hydrogen through the DR reaction means that it takes less time overall to remove the remaining water on Venus. Also, this means that if oceans existed on early Venus, they could have existed for much longer than scientists thought. This allows more time for potential life to develop. The research results do not mean that oceans or life definitely existed. Answering this question requires more science.

The need for new missions and observations of Venus is felt. Future missions to Venus will provide some atmospheric surveys but will not focus on its atmosphere. A future mission to Venus, similar to the Moon’s mission to Mars, could greatly expand our knowledge of how the atmospheres of terrestrial planets form and evolve over time.

With technological advances in recent decades and renewed interest in Venus blossoming, now is a great time to turn our gaze to Earth’s sister planet.

Discovery of the brain circuit that manages inflammation

History of the world; From the Big Bang to the creation of the planet Earth

Skin cancer: symptoms, prevention and treatment

The strange ways skin affects our health

A mystery that is solved by the China’s Chang’e-6 probe!

The secret of the cleanest air on earth has been discovered

Xiaomi Pad 6S Pro review

Why do people listen to sad songs?

The biography of Pavel Durov

Why artificial intelligence has not yet succeeded in replacing Google?

Popular

-

Technology9 months ago

Technology9 months agoWho has checked our Whatsapp profile viewed my Whatsapp August 2023

-

Technology11 months ago

Technology11 months agoHow to use ChatGPT on Android and iOS

-

Technology9 months ago

Technology9 months agoSecond WhatsApp , how to install and download dual WhatsApp August 2023

-

Technology11 months ago

Technology11 months agoThe best Android tablets 2023, buying guide

-

AI1 year ago

AI1 year agoUber replaces human drivers with robots

-

Humans1 year ago

Humans1 year agoCell Rover analyzes the inside of cells without destroying them

-

Technology11 months ago

Technology11 months agoThe best photography cameras 2023, buying guide and price

-

Technology11 months ago

Technology11 months agoHow to prevent automatic download of applications on Samsung phones